|

FALL SEVEN, RISE EIGHT. A Kaizen Approach to Law Enforcement Training & Life by Michael G. Malpass

Book List & Research Studies by Chapter: CHAPTER 1 References:

Feldman Barrett, Lisa. How Emotions Are Made. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York, 2017. Huberman, Andrew. (Host). (2021-Present). Huberman Lab [Video Podcast]. https://hubermanlab.com CHAPTER 2 References:

CHAPTER 3 Resources: Feldman Barrett, Lisa. How Emotions Are Made. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York, 2017. LeDoux, Joseph. The Deep History of Ourselves: The Four Billion Year Story of How We Got Conscious Brains. Viking, 2019. Bilalic, Merim. “The Neuroscience of Expertise.” Cambridge University Press, 2017. CHAPTER 4 References:

Schwarzlose, Rebecca. Brainscapes. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021. Sapolsky, Robert. Behave. Penguin Books, 2017. Mlodinow, Leonard . Elastic. Vintage Books, 2019. Feldman Barrett, Lisa. Seven And A Half Lessons About the Brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020. CHAPTER 5 References:

CHAPTER 6 References:

Resources: Huberman, Andrew. (Host). (2021, March 8). Master Stress. [Video Podcast]. https://hubermanlab.com/tools-for-managing-stress-and-anxiety/ Mlodinow, Leonard. Subliminal. Vintage Books, 2012. CHAPTER 7 References:

Feldman Barrett, Lisa. How Emotions Are Made. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York, 2017. LeDoux,Joseph. Anxious. Viking, 2015. Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind. Pantheon Books, 2012. CHAPTER 8 References:

Resources: Malpass, Michael. Taming the Serpent: How Neuroscience Can Revolutionize Modern Law Enforcement Training.Ockham Publishing, 2018. Feldman Barrett, Lisa. How Emotions Are Made. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York, 2017. LeDoux, Joseph. Anxious. Viking, 2015. Mlodinow, Leonard. Subliminal. Vintage Books, 2012. Gazzaniga, Michael. The Consciousness Instinct. Brilliance Publishing, 2018. CHAPTER 9 References:

Eagleman, David. Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever Changing Brain. Pantheon Books, 2020. Bilalic, Merim. The Neuroscience of Expertise. Cambridge University Press, 2017. Adams, James. Conceptual Blockbusting. Basic Books, 2019. Doidge, Norman. The Brain That Changes Itself. Penguin Life, 2007. CHAPTER 10 References:

Andrew Huberman. (Host). (2021, Feb 15). Learn Faster. [Video Podcast]. Huberman Lab. https://hubermanlab.com/using-failures-movement-and-balance-to-learn-faster/ Chapter 11 References:

Davis, Tchiki . “15 Ways to Build a Growth Mindset.” Psychologytoday.com. April 11, 2019. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/click-here-happiness/201904/15-ways-build-growth-mindset CHAPTER 12 References:

Silver, Nate. The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail–But Some Don’t. Penguin Books, 2015. Pinker, Stephen. Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters. Viking, 2021. CHAPTER 13 Resources: Duke, Annie. Thinking in Bets. Penguin Random House, 2018. Pinker, Stephen. Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters. Viking, 2021. Ellenburg, Jordan. How Not to Be Wrong: The Power of Mathematical Thinking. Penguin Books, 2014. CHAPTER 14 References:

CHAPTER 15 References:

Hofmekler, Ori. The Warrior Diet: Switch on Your Biological Powerhouse For High Energy, Explosive Strength, and a Lenaer, Harder, Body. Blue Snake Books, 2007. Vickers, Joan. Perception, Cognition and Decision Training. Human Kinetics, 2007. CHAPTER 16 References:

Ericsson, Anders, Robert Pool. Peak; Secrets From The New Science Of Expertise. Mariner Books, 2017. Bilalic, Merim. The Neuroscience of Expertise. Cambridge University Press, 2017. Greene, Robert. Mastery. Penguin Books, 2013. CHAPTER 17 Resources: Malpass, Michael. Taming the Serpent: How Neuroscience Can Revolutionize Modern Law Enforcement Training. Ockham Publishing, 2018. Bilalic, Merim. The Neuroscience of Expertise. Cambridge University Press, 2017. Ericsson, Anders, Robert Pool. Peak; Secrets From The New Science Of Expertise. Mariner Books, 2017. Klein, Gary. The Power of Intuition. Currency, 2004. CHAPTER 18 References:

Bilalic, Merim. The Neuroscience of Expertise. Cambridge University Press, 2017. Zinsser, Nate. The Confident Mind: A Battle Tested Guide to Unshakable Performance. Harper Collins, 2022. Ericsson, Anders, Robert Pool. Peak; Secrets From The New Science Of Expertise. Mariner Books, 2017. CHAPTER 19 References:

Badre, David. On Task: How Our Brain Gets Things Done. Princeton University Press, 2020. Schwarzlose, Rebecca. Brainscapes. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021. McLaughlin, Mark. Cognitive Dominance: A Brain Surgeon's Quest to Out-Think Fear. Black Irish Entertainment LLC, 2019. CHAPTER 20 References:

Lembke, Anna. Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence. Dutton, 2021. Duhigg, Charles. The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House Trade, 2014). Taming the Serpent: How Neuroscience Can Revolutionize Modern Law Enforcement Training by Michael G Malpass

Book List & Research Studies: Bailey, Regina. “Anatomy of the Brain: Structures and Their Function.” www.ThoughtCo.com. Updated March 08, 2017, https://www.thoughtco.com/anatomy-of-the-brain-373479 Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1991. Diamond, D.M. Campbell, A.M., Park, C.R., Halonen, J. and Zoladz, P.R. (2007) The temporal dynamics model of emotional memory processing: A synthesis on the neurobiological basis of stress-induced amnesia, flashbulb and traumatic memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson Law. Neural Plasticity, vol. 2007, Article ID 60803, doi:10.1155/2007/60803 Eagleman, David. Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2012. Gonzales, Lawrence. Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017. Grossman, Lt. Col. Dave and Christensen, Loren W. On Combat: The Psychology and Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and in Peace, 3rd Ed. United States of America: Warrior Science Publications, 2008. Hall, Dr. Christine. “Excited Delirium: What It Is, What It Isn’t and How We Know.” Lecture at the Force Science Institute Certification Course: Principles of Force Science. Phoenix, AZ, September 2016. Jeremiah, Dr. David. The Jeremiah Study Bible: New King James Version. Nashville, TN: Worthy Publishing, 2013. Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. Klein Gary. Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1999. Kotler, Steven. The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2014. Kotler, Steven and Wheal, Jamie. Stealing Fire: How Silicon Valley, the Navy SEALS, and Maverick Scientists Are Revolutionizing the Way We Live and Work. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2017. LeDoux, Joseph. Anxious: Using the Brain to Understand and Treat Fear and Anxiety. New York, NY: Viking, 2015. Lieberman, M. D., Eisenberger, N. I., Crockett, M. J., Tom, S., Pfeifer, J. H., Way, B. M. (2007). Putting feelings into words: “Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity to affective stimuli.” Psychological Science, 18, 421-428. Morin, Amy. “Why Successful People Don't Crumble Under Pressure.” www.Forbes.com. August 7, 2014. https://www.forbes.com/sites/amymorin/2014/08/07/why-successful-people-dont-crumble-under-pressure/ Napoleon, Landon J. Burning Shield: The Jason Schechterle Story. New York, NY: 7110 True Crime Library, 2013. Peter, Dr. Laurence J. Peter’s Quotations: Ideas for Our Time. New York, NY: Quill William Morrow, 1977. Reynolds, Susan. Fire Up Your Writing Brain: How to Use Proven Neuroscience to Become a More Creative, Productive, and Successful Writer. Blue Ash, OH: Writer’s Digest Books, 2015. Sajnog, Chris. Navy SEAL Shooting: Learn How to Shoot from Their Leading Instructor. San Diego, CA: Center Mass Group, 2015 Salomon, Dustin P. Building Shooters: Applying Neuroscience Research to Tactical Training System Design and Training Delivery. Silver Point, TN: Innovative Services and Solutions LLC, 2016. Thompson, George J., Ph.D. and Jenkins, Jerry B. Verbal Judo: The Gentle Art of Persuasion. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2013. Van Horne, Patrick and Riley, Jason A., Left of Bang: How the Marine Corps’ Combat Hunter Program Can Save Your Life. Black Irish Entertainment, 2014. Vickers, Joan N., PhD. Perception, Cognition, and Decision Training: The Quiet Eye in Action. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2007. Vickers, Joan N., PhD., Lewinski, William. “Performing Under Pressure: Gaze Control, Decision Making and Shooting Performance of Elite and Rookie Police Officers.” Human Movement Science, Volume 31, Issue 1, February 2012, Pages 101-117. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21807433 Weisinger, Hendrie and Pawliw-Fry, J.P. Performing Under Pressure: The Science of Doing Your Best When It Matters Most. New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group, 2015. Steadman, Andrew, Major, US Army. “What Combat Leaders Need to Know about Neuroscience.” Military Review, Vol. 91, No. 3, May-June 2011 Johnson, Dr. Richard. “Examining the Prevalence of Deaths from Police Use of Force.“ www.ForceScience.org, 2015. https://www.forcescience.com/2015/10/new-study-reveals-facts-of-police-related-deaths-of-unarmed-subjects/ Fryer, Roland G, Jr. “An Empirical Analysis of Racial Differences in Police Use of Force.” Journal of Political Economy. Forthcoming. 2016. https://scholar.harvard.edu/fryer/publications/empirical-analysis-racial-differences-police-use-force Relevant Case Law for Law Enforcement: Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 (1989) Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. 1 (USSC) (1985) Plakas v. Drinsk, 19 F .3D 1143 (7th Cir. 1994) Russo v. City of Cincinnati, 953 F .2D 1036 (6th Cir. 1992) Deorle v. Rutherford, No. 9917188ap (2001) (9th Cir.) Isom v. Town of Warren Rhode Island, 360 F. 3d (1st Cir. 2004) Scott v. Harris, US 05-1631 (2007) Glenn v. Washington County, 661 F. 3d 460 (9th Cir. 2011) Brown v. United States, 256 U.S. 335 (1921) Byran v. McPherson, (9th Cir. 2009) City of Canton v. Harris, 489 U.S. 378 (1989) Zuchel v. City of Denver, 997 F. 2d 730 (10th Cir. 1993) Neuroscientists who are speaking to people like me, who have been hit in the head…a lot, favor an explanation of the brain as a split processing system consisting of the “thinking/cognitive you,” and the “emotional/feeling you.” The “feeling you” is an implicit bias system that provides fast but not necessarily accurate hunches that guide your behavior. These hunches are more and more accurate as your experience level increases in the endeavor in question.

For example, you wake up in the middle of the night shivering, realize the blankets are off the bed, cover yourself and quickly fall back to sleep. The solution to this problem would come quickly and without a lot of mental effort. But instead, let’s say you are woken up by a smell you can’t identify, then realize your house is on fire. The simple transition of waking up, realizing you are cold and covering up, becomes a lot more complicated. Without adequate experience and under heavy emotional response, a quick but not necessarily accurate guess about what to do next, as in cases where the adults run out of the house and forget to get the children. With no training or experience relevant to the issue, they save themselves and forget the kids until they are safe, the brain calms, and they then realize, their kids are not safe. Daily, we are driven by hunches from the emotional, unconscious system that guide our behavior and decisions. The “cognitive you” is basically lazy and unless driven through attention to perform a task, will usually go along with the hunches provided by the emotional systems. Scientists believe the most important function of the cognitive system is the ability of the “conscious you” to overrule these quick hunches provided by the emotional system. In response to incoming stimuli, each system of the brain asks a different question in order to come up with ideas for how-to guide decision making. The “cognitive/thinking you” asks, “What do I think about this issue?” This process is slower but more accurate than the quick hunches of the emotional system. The “feeling/emotional you” asks, “How do I feel about this issue?” This is a faster, easier answer to process but not necessarily an accurate response. Recently, I have repeatedly heard people from across the political divide say that what they feel about an issue is more important than facts and the truth. These, my friends, are incredibly dangerous lines of thinking because the “feeling you” cares about yourself and people you consider to be part of your in-group to the detriment of everyone else. This is an unconscious driver of behavior and some of the same neurochemicals that enhance your connection to an in-group, can make you downright evil towards anyone in your out-group. We are all driven by these systems and a lack of understanding of these systems is currently driving the vitriol in politics, social media and in our day-to-day existence. A fundamental understanding of these brain systems gives the conscious you the ability to overrule some of the hunches of the emotional system. Now, here is where is gets even more complicated; Without time constraints and pressure, it’s easy to spend time thinking about an issue and seeking facts to guide you to the best idea of the truth regarding the matter in question. But, under pressure and time constraints or excessive emotional stress, the emotional system (where the fight or flight responses are directed) attempts to take control and blood flow goes where the action is. Blood flow to the emotional brain diminishes blood flow to the thinking brain and vice versa. Under perceived threat by either stress or the pressure of a situation, the brain may default to the best guess of the emotional brain. For law enforcement officers or anyone in a perceived or real-life threatening situation, these best guesses can lead to tragedy. Why? Because of the substitution of the easier question, “How do I feel about this?,” instead of the more accurate, “What do I think about this?” When you are scared, overly excited, stressed out or overly anxious, the emotional brain wants to answer the easier question. What is the answer of how you feel about something like a suspect’s hands moving to his waistband area while resisting a lawful arrest? If the answer is, threatened, what do you think the quick hunch will be? Keep in mind that the same processing going on in the officer’s brain is also going on in the suspect’s. The suspect’s brain, under the stress and pressure of the situation, may default to the easier question, “How do I feel?” And, if the answer is, “I don’t want to go to jail.” He fights to keep his hands away from the officer by keeping them close to his body. The suspect thinks, “I can’t be handcuffed if I want to escape.” The officer’s hunch is that the suspect is hiding a gun. And here is the dirty secret; If the emotional brain is overly stimulated past a certain threshold unique to each individual, the emotional brain may tell you and show you exactly what it needs to in order to initiate a survival response. In these cases, the thinking you may be completely shut off momentarily. And there you have the anatomy of a mistake of fact shooting. I wrote the book, Taming the Serpent: How Neuroscience Can Revolutionize Modern Law Enforcement Training, to address some of these issues as I truly believe the future of law enforcement is training geared toward how the brain interprets information and drives decision making. In the course of studying these ideas as they relate to law enforcement, I found the same ideas relevant to every one of us in our day to day experiences. What an amazing opportunity...last year teaching in Montreal and this year teaching in Norway! What a blast..great people, great fun, and the chance to teach with Kevin and Ola and Axel...I am truly blessed my friends!

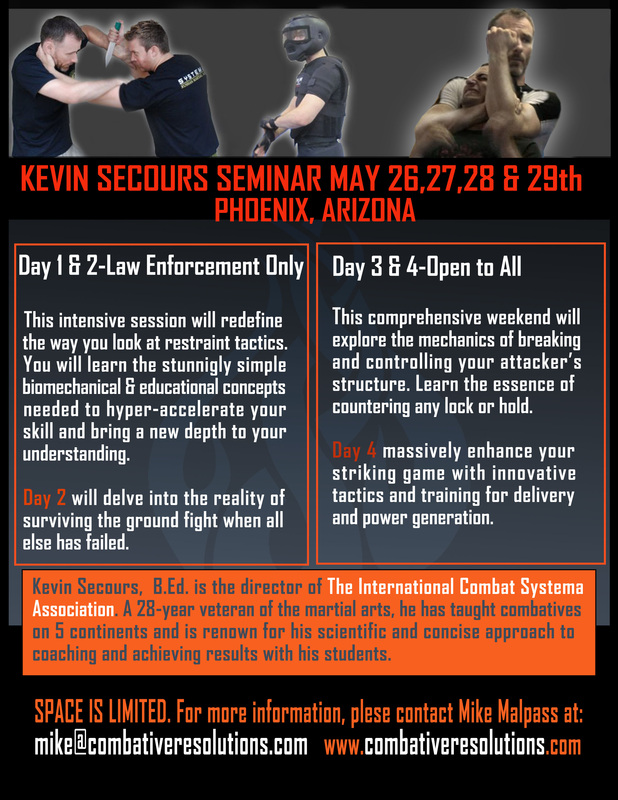

This summer Mike will be a special guest instructor at Kevin Secours' Combat Systema Summer Camp in Montreal, Quebec, Canada during the week of July 9-13, 2012. Here's what Kevin has to say about Mike.

"Mike Malpass of Combat Systema Phoenix will be providing two very special evening sessions. Mike is the owner of Combative Resolutions. He has been a police officer for 19 years, and is currently assigned to the Phoenix S.W.A.T. special assignments unit. He is a five-time national heavyweight kickboxing champion with over 24 years of experience in the martial arts, including intensive training in catch wrestling and defensive tactics. Mike is a progressive, pragmatic, pressure-tested real-world warrior. He will be leading two special evening sessions on Solo and Team Restraint Tactics and Home Security. This is a rare, must-do opportunity to learn cutting edge, battle- proven and street-ready tactics from a man on the frontline." See more about the Combat Systema Summer Camp 2012 here. Posted on June 5, 2011 by Mike Malpass

Last weekend, we completed our first Combat Systema seminar in Tempe, Arizona. The seminar went three days and covered: functionalizing the clinch, takedowns on resisting subjects, ground survival and the Combat Systema striking module. The group consisted of law enforcement officers, Combat Systema affiliates and several people who wanted to compare Combat Systema with other systems they have or are currently studying. First off, what an amazing group of people! Everyone worked hard straight through for seven-hour days. The participants opted for no lunch and small breaks for maximum training time for each individual. Throughout the three day seminar, individuals approached myself and Kevin and commented on the quality of the people involved with the seminar. For the law enforcement officers, it was an eye opening experience to train with Kevin Secours, to be exposed to his extensive experience and abilities and to see an approach to training far different from what the average cop experiences in the course of his/her career. Every cop involved in the seminar made it clear that this style of training is far more beneficial than the standard “cookie cutter” approach to law enforcement training. The affiliates, who have trained with Kevin before said that each time is a new experience and they learn new twists to the lessons each time. The others who have trained in other arts, but not Combat Systema before, were fascinated by the lesson plan objectives and amazed at the extensive knowledge Kevin has, not only of Combat Systema, but of numerous other fighting systems. For me, it was a great experience to be around a wonderful group of people and to spend three days with Kevin Secours, who is not only one of the most skillful and talented teachers I have ever trained with, but a hell of a nice guy to boot. If you have the chance to train with Kevin, I could not give you enough of a recommendation to do so. I can guarantee that you will not be disappointed and you will walk away more poised, more skilled and more amazed each time you train with him. To contact Kevin, go to CombatSystema.com and you can also see some of his teaching methods at Systema Canada on You Tube. I also highly recommend Kevin’s dvd’s, which were my first chance to see the Combat Systema application to fighting systems. Keep in mind, I studied different fighting systems for almost thirty years before I was exposed to Combat Systema material. Here is what I can tell you; if you have already been studying other arts, Kevin’s material will make you better. If Combat Systema is the first art you will study, you will be exposed to a complete fighting system that teaches how to stay healthy and develop principles and attributes from day one that can put you well on your way to becoming a balanced, healthy, and poised fighter. Check on the Systema Canada and Combative Resolutions You Tube pages in the next few weeks for video clips from the seminar and thanks again to Kevin Secours for an awesome training experience. Posted on March 11, 2011 by Mike Malpass

I get a lot of questions regarding why I teach an emphasis on the hammer fist and more unconventional striking methods. Please keep in mind that we can discuss two different methodologies when it comes to striking, which are sportive and combative. I am a huge fan of MMA, boxing, kickboxing and freestyle martial arts and I have competed in all of these arenas in the last thirty years. Eighteen years ago, I became a police officer and since then have been trying to find ways to take my sportive experience and apply it to a more combative application. This has been fun, enlightening, frustrating, confusing and back to exciting, enlightening, and thought provoking. The major issue with sportive striking methods is that the human body can generate more power than the human hand can absorb if contact is not made precisely the same way every time. If making precise strikes was easy, then professional fighters who are involved in street confrontations would have no trouble making the transfer from a sportive to a combative methodology. Unfortunately, this is not the case as numerous incidents involving broken hands with professional fighters both in and out of the ring and cage abound. Don’t get me wrong, I still love traditional boxing and kickboxing striking techniques in their sportive applications. I just don’t endorse using them at full power in a combative application. A worse case scenario could look like this: Imagine a police officer who is involved in an altercation with a combative suspect. They are in a knock down drag out fight and the officer now fears for his life and escalates to full speed full power punching. He manages to knock the suspect down with a mighty overhand right but breaks his hand in the process. The officer is right handed and has now lost the use of his right hand. To make matters worse, three generations of the suspect’s family are now headed his way. The officer is right handed and cannot draw his weapon due to the damage sustained from throwing a picture perfect overhand right that landed slightly off in the fog of war. He cannot quickly handcuff his suspect and make a run for it because handcuffing cannot be done quickly with one hand. Sound bad? This happened to a friend of mine and the only thing that saved him was the emergency button on his radio which brought the cavalry quickly to his aide. If this had happened to an average police officer with no sportive or combative experience it would have been easy to pass off the broken hand as “the cost of doing business.” Fortunately for us, this officer had professional boxing and kickboxing experience and knew the business of sportive striking very well. This gave us a hint that the sportive applications were not transferring to the combative and we began to search to refine our techniques. While discussing this incident with the officer, I remember a conversation I had with Sam Jones back in the 80’s. Sam is a boxing and kickboxing coach in southern Ohio and a high level black belt in Bando. Sam is also a former contender in the professional boxing ranks as well as a holder of numerous kickboxing titles. Sam ran a bar as well as his boxing gym and one night after boxing training we were discussing the fact that Sam had broken his hands so many times that he no longer used traditional boxing punches when involved in conflicts at the bar. We then discussed the Bando Boar punches which are the same as the old school hatchet and hammer fist shots. Sam demonstrated the technique and its many applications as well as how the shots were not as dependant on stance as traditional striking techniques. Sam banged a few of these off my boxing guard and it was amazing how much force was carried through my shielding forearms and into my head. I then used these techniques to get me through my college job of bouncing in the bars at Ohio University in Athens Ohio. They definitely save the hands and there is nothing like a quick, short hammer fist to the top of a free swinging drunks head to make him blink, sag, and become very easy to restrain and escort. No residual effects, no broken bones, just quick disorientation and quick control. It would stand to reason that I would have remembered this valuable lesson and carried it into my law enforcement career, but alas, maturity and common sense came late to this ignorant soul. Roughly fourteen years ago, I brought back the idea of boxing with the hammer fists and have been refining the idea ever since. I have used it on the street and I have used it in the cage and have found it to be equally effective in both realms. Now in the MMA world, I am just a ham and egger. My dreams of sportive glory are over and now I compete when I can because it’s a great way to test the capacity to keep your head and solve problems. My focus now is on techniques that can save my keister when I need them and have less risk of causing injury to myself while throwing them. The hammer fist techniques fit these criteria because it really doesn’t matter what area of the body you hit with them, you can still get an affect out of your opponent. If I go to throw a hammer fist shot and the suspect shields, I can still get an affect out of him. If a traditional punch is shielded, you have a much greater chance of breaking your hand. The hammers can also be easily blended with elbow techniques and tie-ups to create a continuous flow of techniques which don’t require memorization, just familiarization. In fact, while we do drills that have some pattern repetition, each participant is encouraged to find their own flow and blends that work for them. After a short period of familiarization, the hammer fist striking method is easily incorporated into sparring and everyone involved can experience for themselves the effectiveness of the techniques. A good start to incorporating these ideas into your fight strategy is to start on the heavy bag with light shots from numerous angles. Keep the fists tight but the rest of the arm loose and see how many angles you can come up with to hit from. The possibilities are truly endless. Then, do some drilling with a partner back and forth against each other’s shielded arms in order to see that you can bounce them off his shielding forearms and do no damage to yourself. You will also notice how much power carries through your own shielding arms when your partner is throwing. Again, take it easy, no point in giving each other brain damage. The point is to develop a healthy amount of respect for the technique and its numerous applications. When you are ready to introduce it into your sparring, make sure you pad up and wear headgear and a mouthpiece. Even at fifty percent speed and power, you will feel the impact so be careful and enjoy! http://www.youtube.com/user/combativeresolutions#p/u/3/ObY6qzDmPEs Posted on February 20, 2011 by Mike Malpass

If you are reading this blog, then you probably got to this page from Kevin Secours’ blog page or from the Systema Canada YouTube page. (www.combatsystema.com) My thanks to Kevin for showing an interest in the program and for helping promote the idea. I developed the Team Arrest Tactics program around six years ago, after several federal rulings came out against officers who immediately went to strikes in order to solve the problem of a resistant subject who refuses to comply with handcuffing and is hiding his hands underneath his body while lying face down on the ground. The subject may be forcefully moving his body back and forth, but is not actively trying to assault the officers involved in the arrest. To be clear, if the subject is actively assaulting officers, then strikes are certainly a good way to gain control by, first, causing dysfunction, and then, using restraint tactics in order to get the suspect into handcuffs. However, with the subjects who are resisting arrest but not assaulting officers, resorting to strikes is not the most efficient way of gaining control and compliance. While doing the research for the Team Arrest Tactics program, I was speaking with officers from all around the country and finding the average number of flashlight, knee and hand strikes to the arms, back of shoulders and thigh area, to be 15-40 strikes in order to gain compliance. At that time, this was an informal and unscientific study, but the concerns of the federal judges supported these statistics. I have several issues with strikes being the first line of defense for dealing with a resistant but non-assaulting subject. First, while the various strikes are being delivered, the suspect is unrestrained and is able to freely move to defend the strikes, and if he chooses, to begin assaulting the officers. Second, multiple strikes from multiple officers does not pass the headline test. To the average civilian, it looks like a savage attack on one non-violent man by several violent police officers. It does not really matter that they wouldn’t know a good use of force from a bad one because perception does matter. The problem at the time was that officers (including myself) were trained to go to strikes, if, after a “reasonable” amount of time, you were not able to get the hands out for handcuffing. Of course you were on your own to decide what would be a “reasonable” amount of time. The officers involved in the court cases in question acted within the boundaries of their training and within their agencies’ guidelines, so the issue was not excessive force. The rulings usually revolved around agencies seeking a better first procedure to gain compliance before resorting to strikes. From this starting point, the Team Arrest Tactics program began. The Team Arrest Tactics program is a mixture of old school Catch-as-Catch Can Wrestling, Naban Grappling, the Bando Python System and Russian Sambo. The idea was to see if compliance could be gained quickly from a resistant subject by inducing multiple points of pain compliance while inhibiting the subjects ability to take in a full breath. Keep in mind the subject can breathe, they just cannot take in the lungful of air necessary for strong bursts of strength and power. It took around six months of experimentation and the generous support of a handful of police officers who were as interested as I was to see if we could generate some good ideas. This translated to my friends being poked, prodded, twisted, grinded, cross faced and wrapped up like a Christmas gift in order to find out what works. We ended up with a program that was taught in a training module to every officer on my department. Then, it went on to be presented to several other agencies’ specialty details (usually those involved with fugitive apprehension). It’s a fun program that is easy to learn and easy to use. My favorite part of the program is the pace you practice it at is the exact pace to use on the street. The pace is slow and deliberate every time. I did read one post asking if there was concern about restricting breathing. Positional asphyxia is a concern in any arrest situation, but most documented cases come from a prisoner who is already handcuffed and is still combative. At that point, the subject was then “hog-tied” by placing him in leg restraints and connecting the leg restraints to the handcuffs. That places the subject face down on the ground with their legs pulled up behind them and attached to the handcuffs preventing most movements. The Team Arrest Tactics program does place the subject in a similar contortion, but once compliance is gained and the cuffs are on, he is removed from that position. If he is still combative, then a long line is used to connect a leg restraint to the handcuffs, but the subject is able to sit with the line attached and is not placed on his stomach. The subject is also continuously monitored to make sure he does not roll onto his stomach and stay there. The program is designed to inhibit a full breath, but not to prevent breathing. The position is uncomfortable, but in the majority of cases, it is the various forms of pain compliance (which are subtle and not obvious to the average passerby, thereby, passing the headline test) which cause the subject to give up his hands for cuffing. In only a small number of uses have the subjects been able to resist the multiple points of pain compliance. In these cases, they still gave up due to exhaustion within forty five seconds. Please feel free to contact me if you have any questions regarding the program. |

AuthorMike Malpass, Archives

March 2023

Topics

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed